Solving problems can be viewed as asking a series of questions. The problem itself is this big question that cannot be solved immediately. Each good question you ask inches you closer to a solution of a problem. In this way, you break a big problem that is difficult into many smaller questions that are much easier to answer. When all is said and done, you have gone through this long process to recover this result, but how can you be confident you haven’t made a mistake? In a class, someone has the answer already, but in real life there is no answer key.

One way to gain some confidence in your work is by testing edge cases (sometimes also called limiting cases). Often, the problem you are solving is far simpler when you tune the numbers juuust right. That tuning is an edge case, and if you can compare your intuition from an edge case to your general answer, you can be sure that your answer makes sense at least in that specialized situation.

Examples

I encourage you to try finding as many edge cases as you can for the examples below before revealing my list.

Block on a ramp

Let’s start with something quite simple: a block sliding down a frictionless ramp. We’ll say that the ramp has an angle of incline . Let’s figure out the edge cases where it is easy to find the acceleration of the block (

).

Solution

There are several edge cases which are easy to reason through.

If gravity was turned off (), then we would expect the block to not slide down the ramp at all (

).

If the ramp is not inclined at all (), then we would expect that the block would not slide (

). On the other hand, if the ramp was perfectly vertical (

), then the block would be in freefall (

).

The correct acceleration for this problem is . Testing these edge cases, you can see that both

and

give you

. In the edge case where

, the sine becomes 1 and indeed you get

.

Further, let’s say that you eventually try a harder version of this problem and find the acceleration with friction. Having done this problem without friction, you can then consider the frictionless case as an edge case. So these edge cases can build off of each other as you add more and more complicating effects to your problems.

Atwood Machine

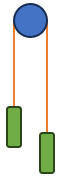

Consider two masses connected by a string and draped over a frictionless pulley. Here, we will think about the acceleration of the mass on the left side of the pulley.

Solution

The simplest edge case is what happens when there is no gravity. In that case, there would be no acceleration ().

Now let’s consider edge cases involving the masses. If the masses are equal to each other, then we wouldn’t expect any movement (). If the right mass was very small compared to the left mass, then it is like there is no right mass, and the left mass is in freefall (

, where I am taking down to be the negative direction). If the left mass was the one that is very small, then it would be like the right mass is in freefall, and the left mass would be accelerated upwards at

.

You can verify that the answer satisfies all the edge cases listed above.

Later on in a first physics class, you might come back to this problem with a pulley that has friction and rotates as the masses accelerate. This problem can be thought of as an edge case of that problem where the pulley has no mass.