Dimensional analysis is a simple, yet incredibly powerful tool in physical reasoning. Physicists use dimensional analysis for a number of reasons: to estimate, to determine what quantities are relevant in a problem, or even to solve a problem outright. Famously, British physicist G. I. Taylor used several photos of the first detonation of an atomic bomb to estimate the size of the bomb, while that information was still secret. He actually gave two estimates of 16.8 and 23.7 kilotons, of which he thought the former was more accurate and the latter was too large. The accepted value of 20 kilotons gives about 15% error on his estimations. That’s not too bad for just looking at a few pictures!

Numbers, physical quantities, and dimensions

Before we can talk about dimensional analysis, we need to make some key distinctions between numbers and physical quantities. If I told you that I was tired from my hike, and you asked me how long it was, you’d be very confused if I said “it was about 13.” The natural question is “13 whats?” because I could be talking about kilometers, maybe I walked for 13 minutes, who knows? This illustrates the difference between a pure number, 13, and a physical quantity, like a distance. The difference is that physical quantities have units, like meters or minutes. These units act as references to connect mathematics to the real world.

Another thing that units do is give a quantity dimension. Not dimension like our 3 dimensions of space, it’s a somewhat unfortunate name. You can think of a dimension as being a certain class of units. Inches and centimeters aren’t the same unit, but they both provide the same dimension, length. There are also dimensions of time, mass, energy, etc. We usually write the dimensions of a quantity by writing the quantity in square brackets, with capital letters representing the individual dimensions. For example, a velocity could be measured in units of kilometers per hour, which corresponds to length (

) divided by time (

):

. Below are some examples of units that correspond to a particular dimension.

Length

- meters

- feet

- miles

- light-years

- angstroms

Time

- seconds

- hours

- fortnights

- years

- millennia

Combining physical quantities

We want to be able to do math with physical quantities. Let’s start with the basics: addition and multiplication. To add two physical quantities together, they must have the same dimension. This should be intuitive. One second and another second make two seconds, and we also understand one hour and twenty minutes. What doesn’t make sense is one hour and 5 meters. This does not apply to multiplication however. You can multiply a physical quantity by any other physical quantity (or even a number). This should also be familiar. If it takes one person an hour to assemble a chair, then the required labor is one person-hour, or if your house draws a kilowatt of power for an hour, the total energy used is one kilowatt-hour. Notice that when you multiply two physical quantities, what you get out has different dimensions than what went in.

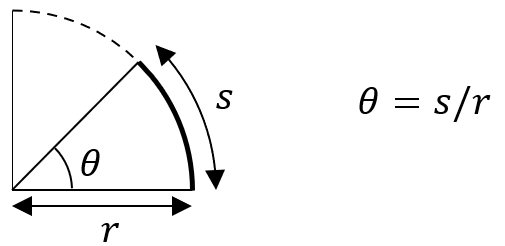

So what if we want to do more exotic things with physical quantities, like exponentiation or putting them into a cosine function? As a general rule, anything more complicated than addition, multiplication, or (sometimes) roots requires dimensionless quantities. Let’s take cosine as an example. Normally, we put an angle into a trigonometric function like cosine, so you might think that something with dimensions of angle can go into cosine. That is because angles actually don’t have dimension! You can see this from the definition of angles in radians, which is given by the length of the arc of a circle subtended by the angle divided by the radius of the circle. As a ratio of lengths, angles must then have no dimension.

If you are familiar with Taylor series, there is another way to see that only dimensionless quantities can appear as the argument of a general function. Take an arbitrary function with Taylor Series

, where the coefficients are all dimensionless. If the argument

is dimensionful, then we are adding up terms with different dimension, since

and

have different dimension.

Doing dimensional analysis

Now we get to apply some of the principles we have seen above to solve problems. The first step is to determine what physical quantities could be relevant. These could be properties of an object (mass, size, etc), fundamental constants (e.g. Newton’s gravitational constant, the speed of light), and more. Sometimes, these physical properties are related, like if an object travels at a constant speed for some time, the time, speed, and distance are related. In that case, we want to throw out physical constants that we can make from others (in the example, one of speed, distance, or time has to go, since it can be made by the other two).

Examples

Now, let’s do some examples. I encourage you to read the set-up and then try to use the principles we have discussed to reason through the problem before reading the solution.

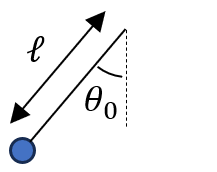

Pendulum

Consider a simple pendulum. It has a length () of string, with a mass (

) on the end. Near the surface of Earth, the pendulum experiences an acceleration downward due to gravity (

). We will hold the pendulum at an angle

and release it from rest. How long does it take for the pendulum to swing back and forth once? We call this time, the period,

.

Solution

The first thing to notice is that there is only one physical quantity that contains dimensions of mass (which is of course the mass), so we can’t expect to use the mass when finding the period. The rest of the physical quantities have dimensions

.

If we want dimensions of time, we will need to use the acceleration due to gravity, but this presents 3 problems: the time is in the denominator, it is squared, and there is a length dimension as well. This isn’t too hard to reconcile, though. The length of the pendulum can cancel out the length units, and then it’s just a matter of manipulating until we obtain one dimension of time on top. The only way this can work is

.

To round out the analysis, we need to account for any dimensionless quantities that might multiply this expression. Since we have a dimensionless quantity in the starting angle, we could have a general function involving this angle:

.

A famous result that you might see in a first physics course is that, when is small (i.e., the pendulum does not swing very far),

.

Doppler Effect

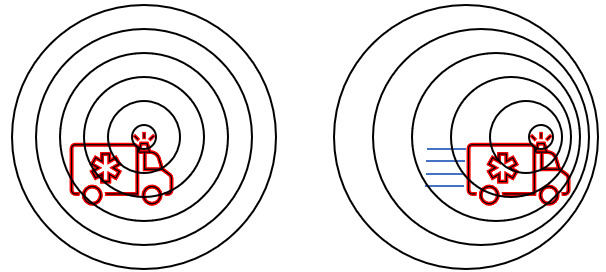

The Doppler effect is a change in the pitch of a sound based on the motion of the source of the sound, like how an ambulance siren sounds high-pitched when it is travelling towards you, and lower-pitched as it travels away. For this example, we will just look at the simpler case of the source travelling directly towards you at a speed . We would like to know the frequency you hear in terms of the frequency emitted by the siren. Below is a picture to visualize the effect. Each circle represents a single compression wave made by the sound.

Solution

Out of all the relevant quantities here, there is only one way to get a frequency, which is from the siren’s frequency, . However, there is a wrinkle in this problem because we can form a dimensionless quantity out of the other variables, namely

. Therefore, we have to allow an arbitrary function of this quantity in our answer:

.

From personal experience, we know that we hear the siren’s true frequency when the ambulance is not moving. Mathematically, that means that . The full solution to this problem is

.

Black Hole

Black holes are objects which are so dense that they form an event horizon, which acts as a point of no return. Anything that enters the event horizon can never escape, not even light, and the more massive the black hole, the larger its event horizon. For a simple black hole, this event horizon is spherical, and it would behoove us to know the radius of that sphere so that we don’t get too close and accidentally get sucked in. So let’s find the radius of a black hole using dimensional analysis.

Solution

The mass must be a part of this equation, but other than that, it isn’t necessarily clear what other quantities to use. This is where some knowledge of physics comes in handy. There is a fundamental constant of nature related to gravity called Newton’s gravitational constant, , and since light cannot escape (but it is the fastest thing in the universe), we might also need the speed of light,

. Newton’s constant has dimensions

.

Between these three constants, we have only length, time, and mass dimensions, so this should be enough to find the radius of the event horizon. To cancel out the mass dimensions, we can multiply by the mass. To cancel out the dimensions of time squared, we can divide by the speed of light squared. That actually leaves us with dimensions of length, so we are done!

.

I gave the radius a subscript S because it is known as the Schwarzschild radius, and is some number. If you do a careful calculation of the Schwarzschild radius using Einstein’s general relativity, you find that

. The Schwarzschild radius also tells you how much you would have to compact an object before it turned into a black hole. For the Earth to be turned into a black hole, it would need to be compacted down into a ball less than an inch in diameter.